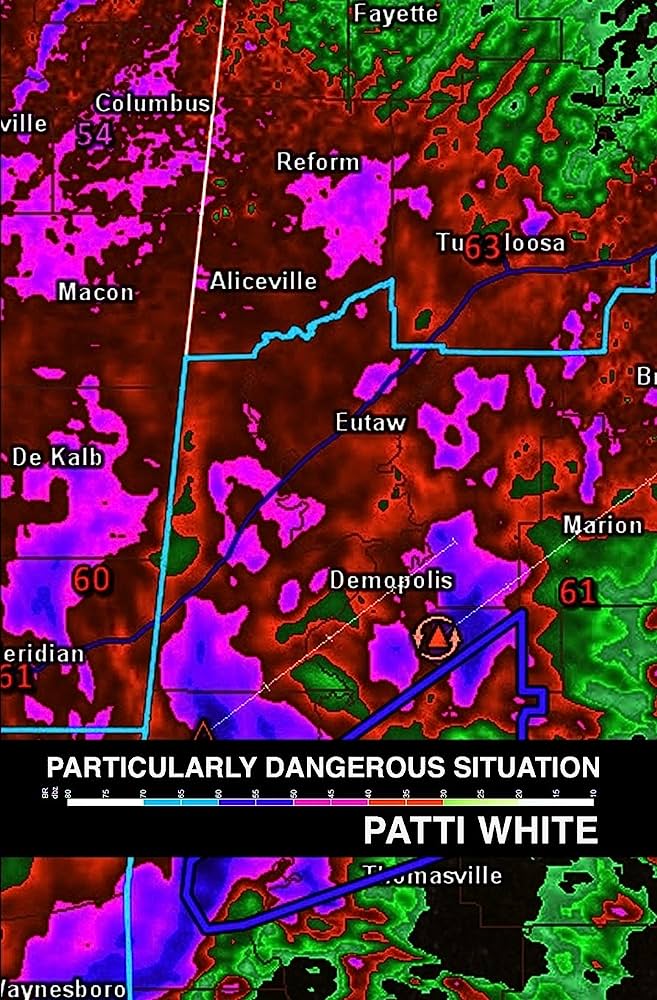

Particularly Dangerous Situation.

Patti White, Arc Pair Press, Tacoma, WA, 2020.

The start of this Alabama odyssey, a novella, is told in a melodic and cyclical way. Yet its content is both and neither. The story is specific and general, told by eight tattered, deranged people. The reader relies on what these characters have or may not have seen because of a barrage of enormous, surreal, and terrifying tornados and storms.

In fact, the irrational juxtaposition of images fits the definition of surrealism. There are excruciating noises, too, and disparate body parts flying through the sky and things human that haven’t been seen, heard, smelled, felt or tasted yet.

The first voice before the storm, Weatherman, announces that “Buildings will disappear. Water will be contaminated. The social order will collapse.”

Carleen Hicks, the next narrator says, “the power went and I could smell the electric sizzle in the walls. And oh the howling.” And when the wind arrives “boards ripping and popping and then the barbeque grill hit the siding…maybe some bones breaking…” Next, “the rain was coming through the ceiling.”

“The roads all sideways and the lines blurred,” reports the next character, Colonel Stanton, who deployed crews for rescue and recovery. “When we drove to Mississippi, we ended up in Louisiana. The trucks went on through like Mississippi wasn’t there…Mississippi is gone…I don’t have any words for what happened there.”

A Mexicano who worked the fields, narrator Juan Reyes, shows an intensely focused, binocular view. When he comes out of the carniceria, “it” was “a poblano swollen and charred…the sky all the wrong colors. It made me sick and I fell on my knees in the parking lot.”

Juan Reyes expresses real and trauma-induced visions: “Across the street the paint store exploded and the power lines snapped and whipped and sparked and everything was coming apart. I crawled through rattlesnakes. The traffic signals dropped like vultures…”

Everett Davis, who considers himself a mathematical and scientific mind has visions of the animal life after the storms are over. “Ambient light from fires on the horizon. And things gleaming in the bushes. Shining eyes. Feral cats or coyotes slinking along…a possum hissing near the dumpster.”

Vesuvia Morris, a sixth narrator, is concerned with the insects, and offers the sense of touch to the novella. “I waited out the second storm in a Japanese restaurant that was abandoned and open to the wind. The sushi station in back was loud with flies and yellow jackets so I sat near the door.” She “wrapped up in a tablecloth” and she felt “chilled. Like seaweed in the ocean. Like shaved ice and dead fish and sticky rice.”

Lila Jane Smith, trapped in a dental chair when the storms begin, and left to watch everything

fall and crash around her, is haunting, as she tells her story: “I am a flying monkey screeching through the clouds. I hear bells clang like a metal drum breaking my ears…sometimes things hit me and I look at my skin for bruises but what I see is shine.”

Tallulah Ballou, late in the story, walks towards a broken library. She comes down a hill “into a chaos of insulation and roofing tiles. Crushed cars in the parking lot… I got lost in Faulkner’s woods, a path forked the wrong way, and oh the mosquitoes and gnats of that magnolia afternoon.” In a commentary, she says, “every plot is subordinate to weather, to summer heat and rain, to the way our bodies respond in the face of barometric pressure.

Earlier in the story, Tallulah Ballou sums up this post-apocalyptic odyssey with uncanny musing: “I am living in a postmodern novel and all the disasters we simulated have come true and still we are not prepared.”

–Mary Jane Ryals