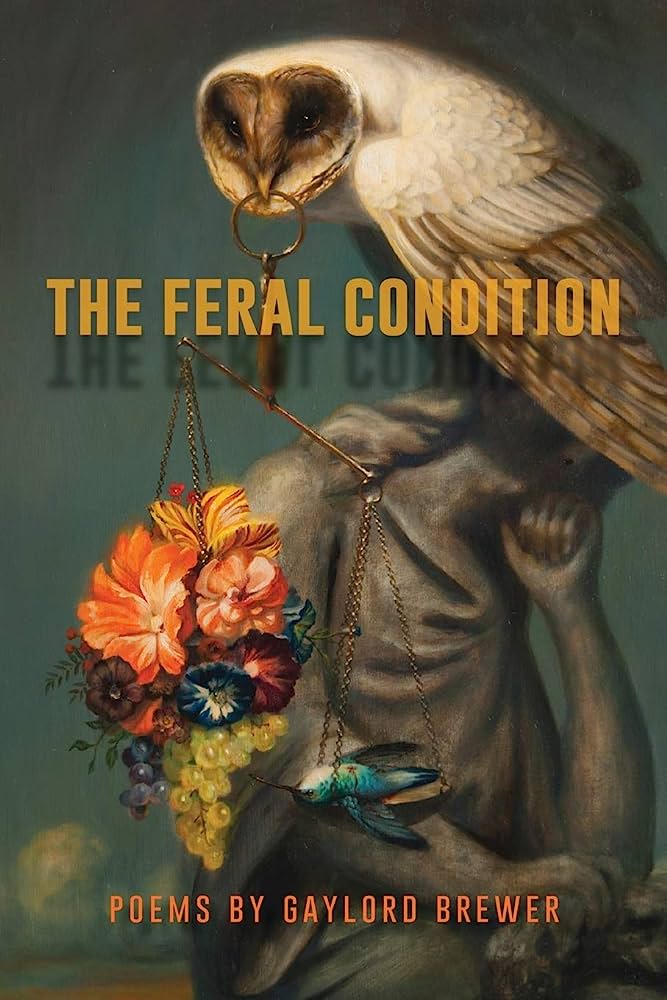

The Feral Condition

Gaylord Brewer. Negative Capability Press: Mobile, AL. 2018.

ISBN: 978-0-94254-440-4

Using a backdrop of four starkly different locales, Gaylord Brewer crafts a journey replete with fables of a man observing and interacting with the natural world, before coming to terms with his own “ferality.” Through language and imagery both striking and candid, Brewer writes to discover and convey universal truths from his observations of the mundane.

The series of bestiary begin with the narrator taking measures to ensure reverential treatment of the natural world, in a sense imitating pure awe; the same as any human might experience when encountering nature. It is not until the second part of the collection, entitled Catalonia, where we see the poet first grapple with the shame of his fondness for the natural world, noted in “The Woman”:

“I hoped she would let me pass so I needn’t announce my ignorance / I confessed the berries I had foraged, the handful of wild rosebuds cut for a vase.”

Here, we see the narrator’s guilt of disrupting the natural order – ripping flowers up from the earth and gathering berries to consume. The poet’s feelings continue to evolve with the collection, as he begins to recognize the mortality and fragility of the physical, and learns to treasure the unseen. This subtle hint of remorse is amplified in “Pyrenees Wild Iris”, in which the poet picks wildflowers off a mountain top for his own joy, likening himself to a slayer. The words themselves hum like William Carlos Williams’ work with its casually apologetic tone.

“I should have let them be

and done no harm, but I couldn’t

help myself, could not:

I had to have them.”

While each poem reads as meditative, the undercurrent that persists is one of a gnawing guilt and an acknowledgment of humanity’s hunger for consumption and violent ownership. As the collection advances, Brewer’s words shift to highlight this preference over brutality:

“Let’s ignore the routine hell of flies

haloing the donkey’s nostrils and mouth.

They’re not pretty, and do we not seek

the picturesque, a narrative of consolation?”

It is a harsh reminder that beauty remains in our grip of an ideal meant to shield us from the grit of reality. The poem, entitled “Exquisite Human Suffering”, ends with a sardonic showcasing of hikers as they stamp upon thousands of ants carelessly, illustrating a tendency to devalue the perceived unimportant:

“What choice but that the big lives stomp

the small? There, just ahead, a spotted fawn

Shoulder-high in mountain clover!

A goldfinch greets with melancholy song!

Meanwhile, every step another bloodbath.”

Brewer brilliantly divides the collection into four stages of being and observance. Each quarter highlights an aspect of man as he learns to reconcile a jaded understanding of himself with his natural position within the world. The poems themselves are carefully pieced in such a way to effectively communicate the structure of transformation, which builds the confrontation of human cynicism and admiration to an apex at the end of “The Owl”:

“Foolish man. You know nothing

of the wild world. Go from this place.

Go home, if you’ve yet one to go to.”

Finally back home, we see the narrator delight in the regain of control before ultimately coming to terms with his hypocritical folly. It is the ending destination, however, of Costa Rica which finds the narrator having completed an arc, existing in acceptance of one’s small place in the ticking rhythm of the natural world. Brewer’s last lines echo this realization of perpetual cruelty blended into humor and beauty that is the feral condition and leaves his reader a simple outcome amidst all anguish: to rejoice and persist.

–Noelle Kennady