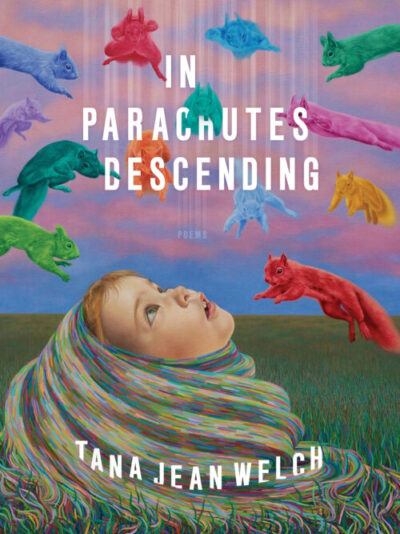

In Parachutes Descending.

Tana Jean Welch. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA. 2024.

Tana Welch interlaces sea level rise, the concept of Seasteading, and stanzas packed with intense passion in her new collection In Parachutes Descending. What makes this book so striking is the narrators’ determination to shift the rules and norms of our culture, our society, our world. She implies that if we don’t do this, we will never be able to save the planet, much less ourselves.

The book opens with “Boston under Water by 2100,” where “the sea / will claim this reclaimed land, / sending these few fragments forever // to the drink,” and then interlaces in each of its next four sections either references to the giant gyre of garbage that haunts the Pacific or the concept of Seasteading (ocean-based permanent dwellings or floating towns independent of established governments). Mixed into these roiling concerns boils passions both surprising and edifying.

The Seasteading, though initially implied as a sustainability-oriented and perhaps utopian solution to address Earth’s ecological crisis, unfolds as something edgier. The proponents of the concept reveal in Welch’s lines “an animal kingdom of jealousy // as [they fear their] own exclusion // and the inclusion of all // others // in parachutes descending.” The seasteaders may pack more of a fierce individualism instead of a welcoming, collectivist spirit.

For example, in “Seasteading: Entrepreneurial Opportunities” we’re told “on the sea they might sell fish / to passersby on boats / or . . . / to other like-minded people afloat,” but by the poem’s end these seasteaders “might not sell it at all / but fry it on a Friday, / swallow as much as they can // and bury the rest at sea.” Moreover, in “Seasteading: Recruiting” a recruitment survey asks a series of unexpected questions ranging from “Do you own a timeshare?” to “What is the total value of your real estate assets?” The survey’s penultimate line demands “Do you have plenty of money?” This series of poems interspersed throughout the collection suggests that if these floating cities become the answer, the city’s themselves might need to fall outside social and even moral norms.

And if seasteading might be a possible but problematic way to save the planet, what about ourselves? How will we save our own bodies and spirits first?

A shove against society’s heteronormative social norms and biases burns its way throughout these pages as well. Starting with titles such as “‘Jesus Died on the Cross Because He Forgot His Safe Word’” and lines like “Last night I thought of you / while Jane slow-worked her tongue / and fingers, slow within / me an electric kistka dripping / beeswax,” the poems show a narrator fearlessly breaking free from an ex-husband, a grounded sense of place, a previous way of life.

The narrator here so often thirsts for change in these poems, asserting how “Again I mutate as we move through / the old park, ready to launch / past the spectral-fired flowers” at one moment and the next absorbing how “Jane Complains . . . // she wants a new glory hole // [but] when she’s angry her voice is clanging / bangles . . . so I hear new glory hole instead / of new gallery and wonder if it’s mine or hers / that’s suddenly inadequate.” In the end the narrator asserts “things can always go differently.” The voice here consistently notes how breaking norms, rules, systems can push a human into a new and perhaps better place, even if the change is a passing through a kind of fire, a singeing “like a courtier devouring, like / a dancer caught fire” a change where we can “heed the transformation as resuscitation” and, ultimately, save ourselves.

–Michael Trammell