It was mid-morning on a Tuesday, and already I was in danger of being late for work when I heard Enrique call my name from the bathroom. I pulled on my uniform shirt and felt the slick film of grease grime coating the front and still smelling like the chicken fryers. I hadn’t been able to scrape together enough quarters for the laundry but decided it was fine, that no one would notice. After an hour on the line, we all smelled the same. Enrique had already been in the bathroom a long time. He had a tendency to linger in the shower until all the hot water had run out. I learned a long time ago to take my showers at night and keep my deodorant and toothbrush in my bedroom. Steam heat from the shower escaped around the door’s edges where it didn’t sit quite right in the frame.

“Your dick better not be out, man,” I said.

“Dude, I was taking a shower, so my dick is going to be out.” There was an anxious pitch to his voice that scared me a little. “I need you to look at something on my back,” he said.

At this stage in our lives my being grossed out by the sight of Enrique’s penis was mostly an act. He had a tendency to walk from his bedroom to the bathroom or kitchen half or completely naked. A confidence in his body I always envied.

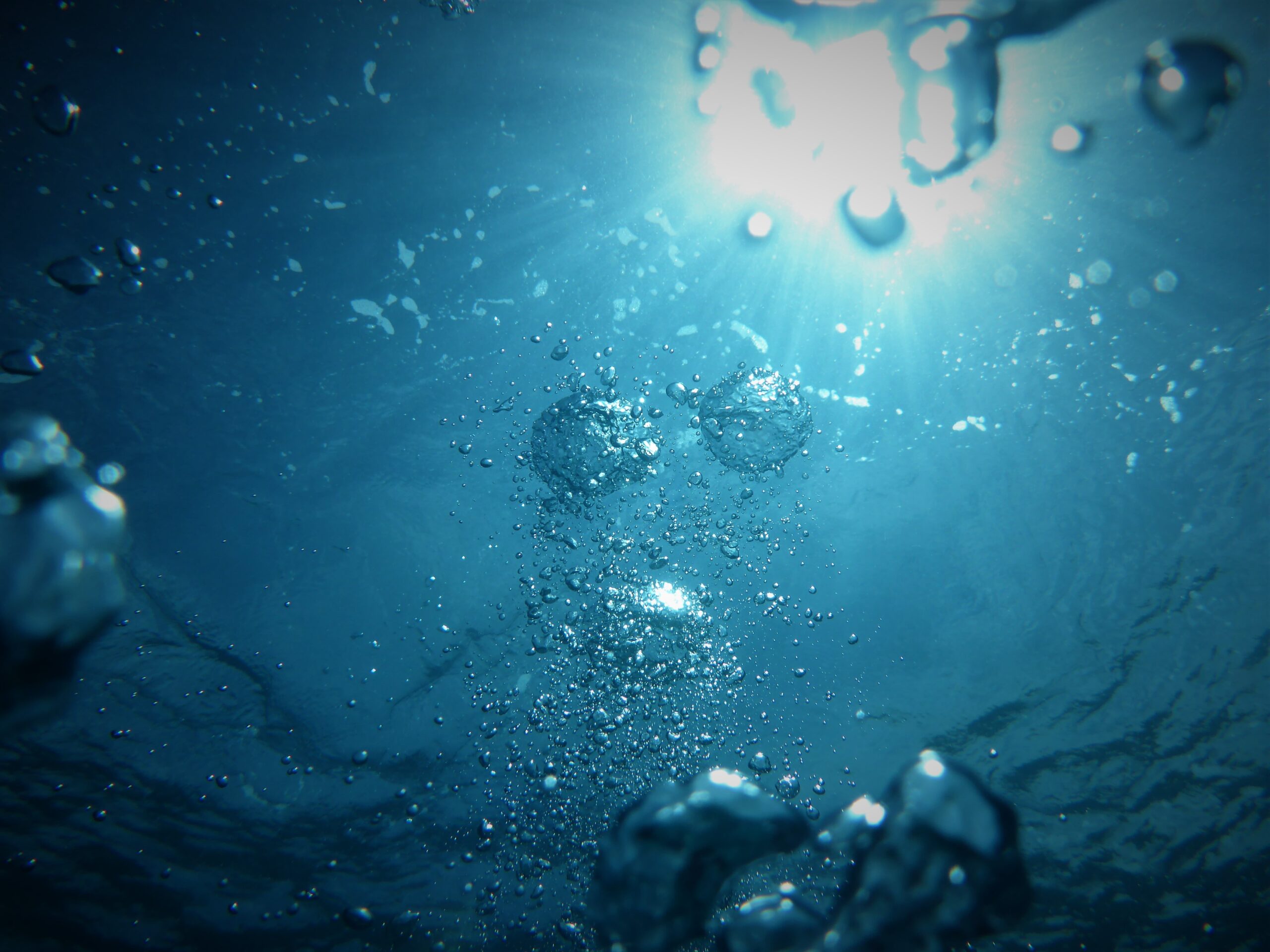

I went in and was buffeted by a bank of steam. Enrique had his back to the mirror and was straining to look into it over his shoulder. He had his hands on his skinny hips as if to keep them straight as he contorted. In the space between his hands was a patch of shimmering water, not bigger than the flavor packet from a package of ramen noodles, at the small of his back. Right where his spine met his ass. Light moved in it in a way that reminded me of a pool in the summertime, clean and clear. I was dazzled by it.

“Can you see it?” he nearly shrieked. “What is it?”

I got close enough to peer into it. It seemed to have depth, but no sides that I could see. The shimmer came from some internal light.

“Can I touch it?” I asked.

“What the fuck is it?”

With just the pad of my finger, I touched the spot. There was tension to the surface, like the skin that forms on jello, and it was slick and cooler than the air around us.

“Do you feel that?” I asked.

Enrique had gone quiet as soon as I touched the spot.

“I feel it,” he said. “But it’s different, not like touching my skin.”

I traced a letter on the spot.

“Could you tell what that was?”

“A letter C?” Enrique said.

“How about now?”

“A.”

“Now?”

“M––Dude, are you writing your fucking name back there?”

He whipped around, holding a towel balled up against his crotch. He was in no mood for jokes.

“It didn’t stay,” I said.

“It better not have.”

Where I had touched the shimmering spot the pad of my finger came away wet, as if I had just run it over an ice cube.

“What are you going to do about it?” I asked.

“I don’t know, man. I tried to peel it, but it don’t come off.”

“Does it hurt?” I asked.

“It just feels weird. Where are the band-aids?”

I rummaged through the cabinet and found an old box of bandages. He turned his back to me, and I tried to put several of them over the spot. It was useless; each one fell off without ever sticking.

“You still smell like fish,” he said.

“It’s not that bad,” I said. “I don’t think you’re going to get anything to stick to the wetness,” I said.

“Throw some baby powder on it.”

There was a box under the sink with baby powder, some gauze, and an ace bandage. They all came out of my parents’ bathroom years ago and hadn’t been used since. I took Enrique out to the couch and had him lie down on his stomach. The water absorbed the powder almost immediately. I shook more on until it didn’t readily dissolve, then pressed the gauze over it, taped it all down with medical tape, and wrapped the ace bandage around his waist for good measure.

Enrique and I were raised like brothers after his mom left. His dad––my mom’s younger brother––took what savings they had and went on a cross-country chase to bring her back. It felt like our entire childhood that Uncle Rob was away, when in truth it was maybe a couple of years. For all that time, he was chasing her from one place to the next while Enrique came to live with us. Even in the end, when Uncle Rob returned empty-handed, Enrique stayed with us. And after his dad came back, he stayed with us. We didn’t know why, but we really didn’t care. We were just happy to be together. When our parents died, all at once in the same car accident, it only made sense to stick together.

My entire shift I thought about Enrique. I pulled baskets of fried chicken and fish out of the fryer and watched the translucent surface of oil settle thick and shiny, reflecting in ripples the heating lamps over the drip pans.

He was already home when I got in, sitting on the couch and staring at the blank TV screen. He’d put on a fresh shirt, and there was a dark wet spot at the small of his back that could’ve been sweat, though I knew better. I didn’t want to bring it up in case he didn’t want to talk about it, so I went straight to the bathroom, showered, and changed into clean clothes. He was still sitting there when I came out.

“Bandages fell off an hour into my shift,” he said.

“It’s still there?” I asked.

“Take a look.”

He lifted the back of his shirt. The spot had grown to be as wide as my palm.

“Everyone at work just thought I was extra sweaty today,” he said. “Hauling freight.”

“Any ideas how to fix this?”

“I was just hoping it would go away on its own. It still might.”

“Get down on the couch,” I told him, and he did.

I brought over a sponge from the kitchen and pressed it to his back. In seconds it was damp. A few minutes later it was completely saturated. I got a pot and squeezed the water into it, then pressed the sponge to the spot again. Each time I touched the spot, Enrique tensed but said nothing. Where my fingers grazed his back, his actual skin was feverish by comparison, while the water was surprisingly cool. I wrung the sponge out over and over again for I don’t know how long, but the spot didn’t shrink.

“Stay there,” I said.

“Is it getting better?” he asked.

I didn’t answer. During my shift at the Chicken Hut, I had to quench a grease fire with a bowl of dredging flour. It made me think to get every dry thing we had, the remnants of baby powder, flour, bread crumbs, baking soda that came from I don’t remember where. I doused the spot liberally with one after another, and each new substance turned to a clayey mess on his back that I then scraped away before dousing again. After everything was exhausted, the spot remained.

Enrique stood up from the couch and put his shirt back on.

“It’s okay, man,” he said. “You tried.”

Every day after that the spot spread. In a week it filled the small of his back. We tried everything we could think of, but nothing reversed his condition. The spot didn’t drip on its own, but wherever his clothes touched slowly started absorbing moisture until they couldn’t hold anymore. When his shirt was fully saturated it started to drip. It was getting difficult for him to hide the wet spots on his shirt or to explain them away.

I was watching TV when I got the next idea. A commercial showed a jet of blue-colored water hitting cotton, and I was out the door. The cashier at the CVS was only a little confused that I was buying so many boxes of maxi pads at once. I had no idea how many would do the trick. We’d never had any sisters, and I never had a girlfriend steady enough for her to send me to the store for that sort of thing. Nonetheless, I was more than a little proud of myself when I dropped the bag on the coffee table in front of Enrique.

“No fucking way, dude,” he said.

“This will work.”

“I’m not on my goddamn period.”

“Don’t be an asshole,” I said. “What parts of maximum absorbency and extra heavy flow don’t you understand?”

“I wouldn’t call this an extra heavy flow,” he said in a low voice.

“All the better then.”

It took a little more convincing, but eventually Enrique agreed to a test run. Two pads were wide enough to cover the spot. We stuck them on then secured them with the ace bandage just to be safe. After a couple of hours only the tiniest wet spot appeared on his shirt.

“I think this is going to work,” I said.

“How long do I have to put these on, you think?”

“Until whatever it is runs its course, I guess.”

We used to play this game some nights when we were kids, in the years when Uncle Rob was away. My parents had a stash of buckets stored under our trailer. Most of them had a big golden “M” printed on the side, and all of them smelled like pickles or onions. We knew we were about to play if at twilight my dad started to drag the buckets out and pry open their tops. Enrique and I would run tight little circles in the middle of our room, pumping our skinny little arms to psyche ourselves up. Then Dad would call us into the living room.

“Which of you is the strongest?” my dad would crow into his fist, pretending he was holding a microphone.

In response, Enrique and I flexed our muscles like we’d seen contestants do on American Gladiators.

“Which of you is the fastest?”

Enrique and I kicked our scrawny legs in the air as fast and as high as we could, as if that would prove it.

“Which of you is the most silent?” Dad would say in a theatrical whisper.

We both turned our heads side to side, a finger to our lips like we were hushing an imaginary crowd and each other.

“We will let the contest decide!”

My dad’s arm shot up, and that was the signal for us to start. And we ran out the door and into the night.

The rules were simple: we each carried a smaller bucket and had to run to the neighboring trailers, fill our buckets with water from their spigots without getting caught, then run back and dump the contents into the larger buckets. We couldn’t cheat by trying to make the other spill and we couldn’t visit the same trailer twice in a row. We did this until the large buckets were filled. Then dad would close them up again and slide them under the trailer and replace the siding. He never declared a winner but told us how great we had both been.

Later we’d use that water for cooking and cleaning, for bathing and for laundry. For years our clothes always had a briny smell, which I loved because it reminded me of a cheeseburger. It was a long time before I realized we did this because our water got shut off for not paying the bill. I wondered how long it was before Enrique figured it out. We never really talked about those days, not in terms of what we lacked.

The maxi pads worked for a while, but the spot on his back kept growing. We tried to stay ahead of it and were doing alright until one day a fully saturated pad fell out of Enrique’s shirt and onto the sales floor, right in the middle of a team meeting. There was no explaining that to everyone.

I was home for lunch in the middle of a swing shift. The general manager at the Chicken Hut was nice enough to give me some additional hours after I told him Enrique was sick. I didn’t give him the details.

“I felt it go, but thought it would get caught up in the bandages,” he said to me, pacing in front of the TV set.

Behind him, two teams of cartoon superheroes were fighting each other. They’d been tricked into conflict by the actual villain, who used the distraction to commit some real evil. I was tired and annoyed, trying to pay attention to both things at once.

“It hit the floor and made a loud wet slap. Everyone heard it and just stared at the thing like it had come out of me or something.”

The cell phone we shared rang from where it sat on the coffee table.

“I didn’t know what to do, man. I just left.”

He looked at the caller ID and snatched up the phone.

“Hey, Judy,” he said into it. “Yeah, I was really sorry to do that, but it was an emergency.”

He continued pacing. In his pauses, I could hear the tinny voice of his boss in the sad little receiver.

“Yeah, the sweating thing,” he said. “It’s more than that really.”

He paused for her to speak.

“No, listen. I’m going to the doctor soon.”

Another pause.

“I get that, but I need this. Please.”

Enrique was quiet long enough that I went back to watching the TV. It bothered me that the heroes were still fighting one another. They just seemed angry, and I suddenly thought about how everything they did, including saving the world, seemed to be motivated by that anger. It all felt like a colossal waste of time.

“Yeah. Sure. As soon as I know, you’ll know.”

He hung up and whipped the phone into the couch cushions.

“Yeah?” I said.

“Shit.” He stared at the place where the phone had disappeared into the couch as if willing it all to rewind. “That was a good job. I was in line to be a shift manager and everything.”

“I thought you said Judy had a crush on you,” I said, as if that was something he could leverage.

“Obviously I was lying,” he said. “I did have a crush on her though.

“Well there goes your shot,” I said.

“No shit. If this thing clears up by the weekend, I’ll go see about getting my job back.”

When I didn’t answer, he just shrugged and made a move to sit on the couch beside me.

“Hold on,” I said.

I jumped up and went to the closet and pulled out the plastic we use to cover the windows in winter and spread it out on the couch for him to sit on. Enrique stood, staring at me smoothing out plastic. A wet spot formed on the floor around Enrique’s feet where the water dripped from the back of his shirt.

“You afraid I’m going to ruin the couch now?” he said.

It wasn’t a nice couch. Just something we’d picked up from the college when all the school kids went home from the dorms. It was already starting to smell a little mildewy from where Enrique had soaked in before. A lot of our furniture had come from those kids’ rich parents. Probably they weren’t even rich, but that’s how we thought of them. The couch was maybe a hundred dollars new from Walmart. Who else but rich people could afford just to throw away a hundred bucks?

“I’m just trying to keep it dry, man.”

“Whatever. I’ll just stand forever, I guess.”

“It’s not a big deal. Just sit on the goddamn plastic.”

“No big deal? You try dealing with this.”

Enrique launched himself at me like he was flopping into a pool. I tried to get my knees up to keep him off, but he got onto my lap. There was a wet slap when his water-back hit me, and I could feel the cool slick moisture of it. I shoved at him with my forearms, the give of his back making me afraid my hands would push right into him. We wrestled like that, not throwing punches––we never hit each other––just a lot of shoving and throwing our weight around.

“How does it feel?” he shouted over and over again.

He rubbed his back on me until I was thoroughly drenched, and I finally managed to topple us both to the floor.

Enrique, face down on the floor, laughed hysterically. He got up and collapsed onto the plastic sheet, and it made a crumpling sound.

“You feel better?” I asked. My shirt and the front of my pants clung to me, but my back half was still dry.

“It is what it is, you know.” He made it sound halfway between a question and a statement.

“Can you feel it?” I asked him. “How it’s wet in the back?”

He sighed like someone who had answered this question a lot of times already, though he hadn’t.

“I can feel the shirt but not the wet. Not until it soaks through to the sides and over my shoulders. Then I can feel it on the parts of me that are still, I don’t know, skin?” he said.

“What then?”

“I get annoyed and just take my shirt off.”

“Why even wear a shirt in the first place then?” I asked.

He turned just his head to look at me. By then the heroes on TV had realized the set up. They were all on the side of justice and good and came to an understanding about one another.

“Honestly, I didn’t want to freak you out.”

“Just be comfortable, man. Don’t even worry about me.”

He looked at the TV for a minute without really watching it. Then he whipped the t-shirt up over his head. He undid the bandage around his torso, and the pads came with it. From the couch, he tossed the whole mess in a sopping ball into the kitchen sink.

Enrique never went to the doctor, and I knew why without asking. It wasn’t even a question. The mere thought of money made my stomach clench. There was always less than you thought. Enrique had been out of work for only a few days. There hadn’t been time yet to feel the effects of his transformation on the bills. I swallowed that dread to deal with another time.

“What I don’t get,” I said to him, three weeks into his transformation, “is why we can’t see your organs and all. I mean, we can see right through your skin, but its like everything is just water.”

“Are you fucking serious right now?”

He was sitting forward on the couch. The water was up over his shoulders now and traveling down his arms. As long as his water parts didn’t touch other surfaces, he didn’t drip. He held a cup of coffee between his hands but hadn’t taken so much as a sip.

“And the shimmer,” I said. “Where is that light coming from?”

“Fuck the light, dude,” he said quietly.

The more I talked, the more the shimmer moved as if in response to an invisible current. I went and sat beside him and put my hand on his slick, cool shoulder.

“It’s getting better, I think.”

He looked deep into his coffee cup like he was psyching himself up for something.

“Do you want me to take that for you?” I asked.

“I’m not finished with it yet,” he said.

“You haven’t even taken a drink yet.”

“I know, I will.”

“Do it then,” I said.

I wanted him to drink it. I wanted to see if the coffee would spill from his gullet into the pristine waters and watch if it would separate and curl like smoke, if it would cloud him over or dissipate into nothing.

Enrique tipped his head back and took a big gulp. His throat worked, and then something went wrong. He made a gurgling, struggling sound and spewed the coffee all over the table in front of him. It wasn’t like he puked; the coffee came up whole. There was no black liquid twisting gently in his water body. In a way that I thought was a little too calm, Enrique picked up his towel from the floor––these days he always kept a towel close by––and mopped up the coffee.

“I guess it just had nowhere to go,” he said.

I was on my way home from another double shift when a thought occurred to me that I was surprised hadn’t come up before. A wetsuit. It would’ve covered most of his body, the parts that were water already at least. We could’ve worked something out for his hands and feet, if it progressed that far. Not that it would’ve been a perfect solution, but it might contain him, let him wear clothes, go back to work, and have a semi-normal life.

At home I went straight to Enrique’s room to float the idea and found him standing at the window with his back to me, looking out. He was completely naked. The water covered the entire back of him. From where I stood, only the back of his head was uncovered. Backlit as he was by the window, the shimmer of water cast its own light into the room. I was hypnotized by the patterns of light moving about more quickly than I had seen before, like something agitated the water.

A pool spread out around his feet, so I knew he’d been standing there a while. I watched him for a minute or so more. The light shifted subtly, and his form relaxed into his normal sagging posture.

“You want to see something?” His voice broke the hypnotic effect of his shimmer.

Before I could say, he turned around, arms out to give a full view of his body. The water had made its way around down his arms and to his fingertips. It encroached on his sides and chest, though there was still bare flesh from his collarbone to his navel. The water covered him from waist to toes as well. Where his penis should have been he was smooth with barely a bulge to suggest anything was ever there. Shape without definition, like the rest of his body.

“I don’t know if it’s related,” he said, gesturing to his body, “but sometimes I have this intense feeling like I’m supposed to be somewhere else.”

“Where?” I asked. A hard lump formed in my throat.

“I don’t know.”

I wanted to say some words of consolation or encouragement but had none.

“You know what I realized today?” he said. “I’m the same age now as my mom was when she left.”

A breath got stutter-stuck in my chest. I hadn’t thought of his mom in a long time. There was no memory of her face for me to draw to mind; she belonged to a time before time. And yet, I could see then a way in which our lives flowed out from her leaving, and was grateful.

“That’s weird, isn’t it?” Enrique said.

One morning, near the end, I heard Enrique calling my name from his bedroom. The call woke me up out of a deep sleep, and I had the feeling that I’d been dreaming of him yelling my name a long time. That I had been hearing it in my sleep and dreaming of being separated from him. His voice sounded strange, like he was shouting around a gag, and the distress of it made me immediately alert.

Enrique was sitting on his bed, blankets balled up around his waist so he looked like he was rising out of them. The sheets and blankets were soaked and dripping in spots on the floor. The smell of mildew was in the air, and the heat from the morning sun made the room humid. I could see he had been crying.

“It’s getting hard to talk,” Enrique said. The words gargled a little in his throat, and he held his chin up as if he could somehow keep above the flood of his own body.

I sat down on the bed. The water went through my shorts instantly, but I didn’t care.

“It’s not going to get better,” he said. A little bit of water came out of his mouth.

I felt the tears welling up. It wasn’t the first time I ever thought of losing him, but I suppose I was also holding onto the hope that this would just go away on its own.

“Maybe it’s time to see a doctor now,” I said.

“What for?” he said. The gurgling forced him to pause as he spoke. “They’re just. Going to charge me. Out the ass. To tell me. They don’t know what this is.”

He stopped like he was catching his breath, but it looked more like he was swallowing. His mouth gulped, and there was no adam’s apple to move, nowhere for the water to go. I waited.

“I googled it before. This isn’t a thing. All I found. Some bullshit. Poetry about oceans.”

I wanted to remind him that there were lots of people smarter and better than us that knew how to do the things we couldn’t. But I knew what he was really saying and decided to let it be.

“Bring me that check. And a pen,” he said.

His paycheck was open on his desk, uncashed. I grabbed what he asked for and a solid surface to write with. As soon as he touched the pen to the check beads of water ran down onto it. He yelled for me to snatch it away before it got ruined, and I did. I pressed the paper between the folds of a towel like you might try and dry a flower. It was still readable. We waited for it to dry, then I forged his signature and signed the check over to myself. It was almost five hundred dollars.

“I have money. In my account. We can transfer it. To you. Forge my name. On the papers. To the trailer. I’m signing that over too,” he said.

“We don’t have to do this right now,” I said.

Things were happening so fast just then. I regretted not considering earlier that as his body was consumed he might disappear with it. If he couldn’t speak and didn’t have his face and didn’t need to eat or drink, was he still Enrique? He didn’t seem to think so.

“Yeah. We kind of do,” he said.

“Give me a minute,” I said. “I’ll meet you in the living room.”

I went back down the hall and to my room. I had the cell phone with me all the time now. He had no use for it. My shift was supposed to start in a few hours, but I figured I would call in right away, give them time to find coverage. What I told them wasn’t a lie exactly, saying that Enrique was hurt and I needed to take care of him. All the emotion stopped my voice when I said it, and that was all the convincing my boss needed.

Enrique was on the couch waiting for me when I came out. He had put down the plastic. Being made of water, his posture looked relaxed even though his face was all screwed up with emotion.

“I put the papers there,” he said, pointing to the coffee table. A pair of barbecue tongs lay beside the paper. He must’ve used them to keep the paper dry.

“I’ll sign them later on.”

“Sure,” he said. “You can sell if you want. That won’t hurt. My feelings.”

I didn’t know what to say so I didn’t say anything. We sat like that for a while, with me trying to think up anything good, trying not to think of this as Enrique’s final moments.

“Is there anything you want to say?” I asked.

He thought about it and moved his lips. There was a little bubbling sound, and a trickle of water ran briefly out the corner of his mouth. The water was up under his chin like a turtleneck. I hadn’t even noticed it creeping up.

He lasted a few more days after that. The water traveled up the back of his head and around behind his ears. It was eerie seeing his face on this body made of water, like a patch of flesh just stuck on. What made it weirder still was that he didn’t open his mouth anymore. He just squeezed his lips together the same way you do underwater when you’re trying to hold your breath. It seemed peaceful like they say drowning is supposed to be.

I expected the change to continue more gradually, closing around the remainder of his face until it was just his eyes left. But one morning I woke and there was this watery phantom standing at the window staring out. The shimmer would move like crazy one minute and then become placid. I had thought I would be scared of the being he would become in the final stages. Seeing him there at the window was strange, but the way he stood still reminded me of Enrique.

He’s still here, though sometimes I forget it. I see him move wraithlike through the apartment. His footfalls make the barest squish and suction sound as he goes, but that’s it. He never sits, on the furniture or anywhere, anymore, and I don’t know if he even sleeps. Most of the time he’s standing there at the window with the door open. The light through the window passes through the prism of his liquid form to dazzle on the wall behind, the opposite of shadow, a human shape of moving color and light. I know there’s someplace pulling on him and I wonder if it’s me keeping him here.

Tim Buchanan is a writer and teacher living in Kalamazoo, MI. His writing imagines the fantastical and strange hidden just under the surface of our mundane world. Other stories have appeared in Puerto del Sol, Bull: Men’s Fiction, and elsewhere.