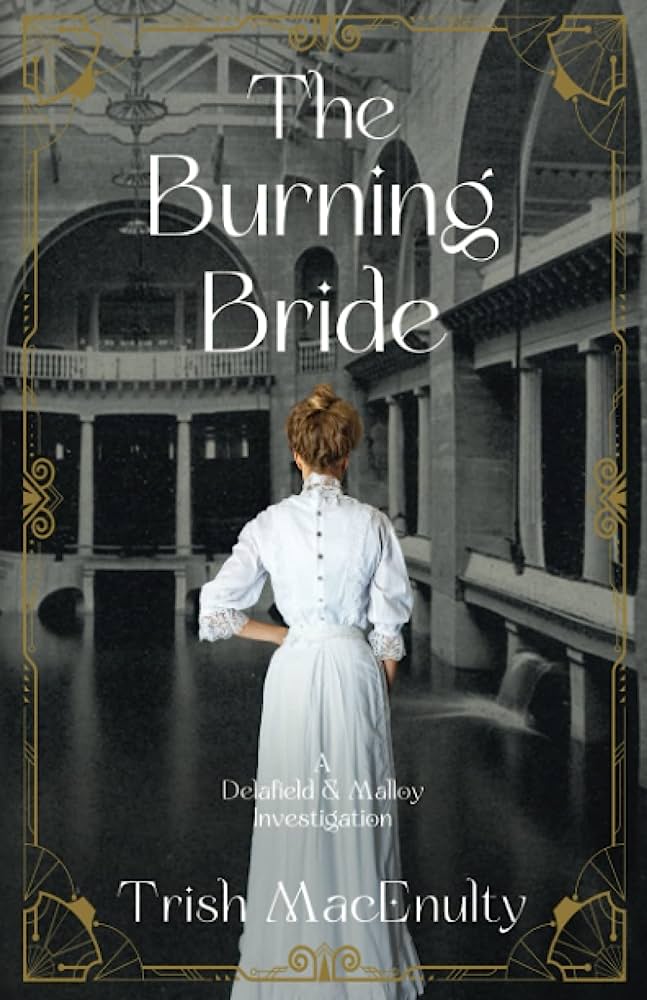

The Burning Bride

Trish MacEnulty. Prism Light Press: Tallahassee, FL., 2022.

Trish MacEnulty’s novel The Burning Bride sparkles with a high-energy plot and tight, precise prose. And what makes the book especially fascinating is the carefully researched details of early 20th-century New York City and St. Augustine. This book uncovers forgotten facts about the New York populace’s fears of anarchists’ bombings and shootings, St. Augustine’s Henry Flagler-built hotels, and the northeast’s culture of high society. All these details are filtered through the lens of the intelligent and compassionate narrator, Louisa Delafield.

Delafield is a journalist and, when the situation requires, an amateur detective. Her newspaper sends her on a job to cover a society wedding in Florida, mainly trying to get her out of N.Y.C. where she may have been the target of an anarchist assassin’s bullet. A trip to the south is a good respite for her.

She’s glad to find the society in St. Augustine to be more egalitarian and much more interesting “than the tired system regulated by the grand dames of Old New York.” An acquaintance agrees: “[T]he Astors, the Morgans, the Fishes . . . , [t]hose women have been so busy turning up their noses at new money they haven’t realized that throughout most of the rest of the world, no one cares.” She appreciates that this new guard of young women has “been to college, . . . aren’t signing over their futures to a husband before they turn twenty. . . , [and] know how to have fun.”

Delafield enjoys exploring the magnificent and sometimes luxurious buildings of the small city. Her first encounter with luxury occurs as she arrives at The Florida House hotel, a spot not as famous as The Ponce, but just as hospitable: it has “a steam elevator, and each room has a private bath and electric lights.” And the four-story building’s exterior is even more impressive with its balconies and Victorian garlands atop an expansive veranda. Once inside, she notes the grand lobby has “a stately oak staircase and potted palms gracing the corners.” The interior includes a “large cage filled with noisy, colorful birds . . . [and] [r]attan fans” rotating above the room full of aristocrats.

Juxtaposed with the story of Delafield in Florida is a subplot about Ellen Malloy, Delafield’s assistant and close friend. Malloy manages to infiltrate New York’s lead group of anarchists and others sympathetic to workers’ causes, including Emma Goldman, the Russian-born political activist and writer. Malloy aims to discover who the shooter was who missed Delafield but shot another. However, she realizes her sympathies are mixed because of how much she identifies with the struggling Irish immigrants in the city’s poorer boroughs.

The novel’s major plotline entwines itself around the wedding of the wealthy Daphne Griffin to the Frenchman Henri Bassett, who may be both broke and a scoundrel. The diamond on her engagement is so spectacular that Delafield suspects it may have been one of dozens stolen from a broker in Egypt the year before. When Henri’s friend Lord Wickham, the original purchaser of the diamond, is found dead below his Florida House hotel balcony, the story takes a more complicated turn. Delafield latches onto all these cases, no matter the dangers involved.

Meanwhile, Delafield’s family-helper, Suzie, also has a connection to Florida: some of her kin moved decades ago to St. Augustine’s Lincoln Town neighborhood, an area not known for its ritz but instead for its tradition of being the home of African-American families. Suzie explores this community, and it sparks wishes to reacquaint permanently with the kin from whom she’s been long-separated. This dynamic creates more anxiety for Delafield because she might lose her longtime helper and friend.

With all the tensions between the haves and have-nots, the novel naturally gives a nod to Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady. These pages make plenty of playful indirect and even direct references to the classic. At one point, Delafield asks Wickham “Is Daphne your Isabel Archer? . . . , thinking of Henry James’s unwitting American protagonist.” As with James’s novel, MacEnulty’s work is both a character study of the book’s protagonists and a plot-driven work centered on a clash of the monied and the unmonied-but-faking-it. In MacEnulty’s novel, this clash goes further, pitting the employed up against the unemployed, the powerful elite against anarchists, the desperate against the comfortable.

Finally, it’s important to note this book fits into a series, a sequence of investigative narratives with Louisa Delafield as the unofficial but primary detective. Lovers of historical novels with a mystery at their core would be wise to keep up with these terrific books.

–Michael Trammell